Especially for the Targets of PsyOps: You & Me

“Assumptions are dangerous things to make, and like all dangerous things to make — bombs, for instance, or strawberry shortcake — if you make even the tiniest mistake you can find yourself in terrible trouble. Making assumptions simply means believing things are a certain way with little or no evidence that shows you are correct, and you can see at once how this can lead to terrible trouble. For instance, one morning you might wake up and make the assumption that your bed was in the same place that it always was, even though you would have no real evidence that this was so. But when you got out of your bed, you might discover that it had floated out to sea, and now you would be in terrible trouble all because of the incorrect assumption that you’d made. You can see that it is better not to make too many assumptions, particularly in the morning.”

-Lemony Snicket, The Austere Academy

Last time I wrote about What we can know and epistemology, the philosophy of knowledge. This time I write about the value of the ‘working thesis’. A working thesis is the opposite of an assumption. It is a proposition that you assess as MOST LIKELY true, however you do not yet have full evidence or an inner conviction to pour it into concrete and make it an axiom, a premise. As a result, all information that reaches you is absorbed in a relatively neutral manner. You subsequently categorize the information in the ‘pro’ or ‘against’ argument list for your working thesis.

Our world today, and the high levels of fear in it, is fuelled by assumptions.

The method of working theses requires a level of emotional detachment, such as the absence of fear, hope or wishful thinking, and it also requires heart-brain coherence: an energetic equilibrium between thinking and feeling, between ratio and intuition. It also follows the rules of logic as they were formulated most eloquently by the ancient Greek philosophers.

During these times, in which Western citizens are the targets of a sophisticated, enduring psychological operation (PsyOp), I think it’s wise to hold almost everything as a working thesis instead of making assumptions.

During this PsyOp, keep in mind that all information that empowers individuals, solves major world problems and limits human suffering is seldom reaching people.

When transforming your assumptions into working theses, consider two fundamental topics:

- Human consciousness: Space and time is not fundamental to consciousness, meaning that, MOST LIKELY, energy exists far beyond what our senses process. What we observe is similar to an internet browser, a purposefully simplified interface but there’s plenty of code behind it. Teleportation, telepathy and other phenomena that operate beyond space and time could therefore potentially exist. Some examples of sources: Cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman, entangled particles Nobel Prize Physics 2022.

- Human civilization is MOST LIKELY much older and much more important and advanced than our history books have been suggesting up until now. This working thesis claims that our current society has been dangerously built on assumptions that urgently need to be reassessed. The amount of arguments supporting this thesis is rapidly accumulating. Sources: Graham Hancock, Randall Carlson and many others.

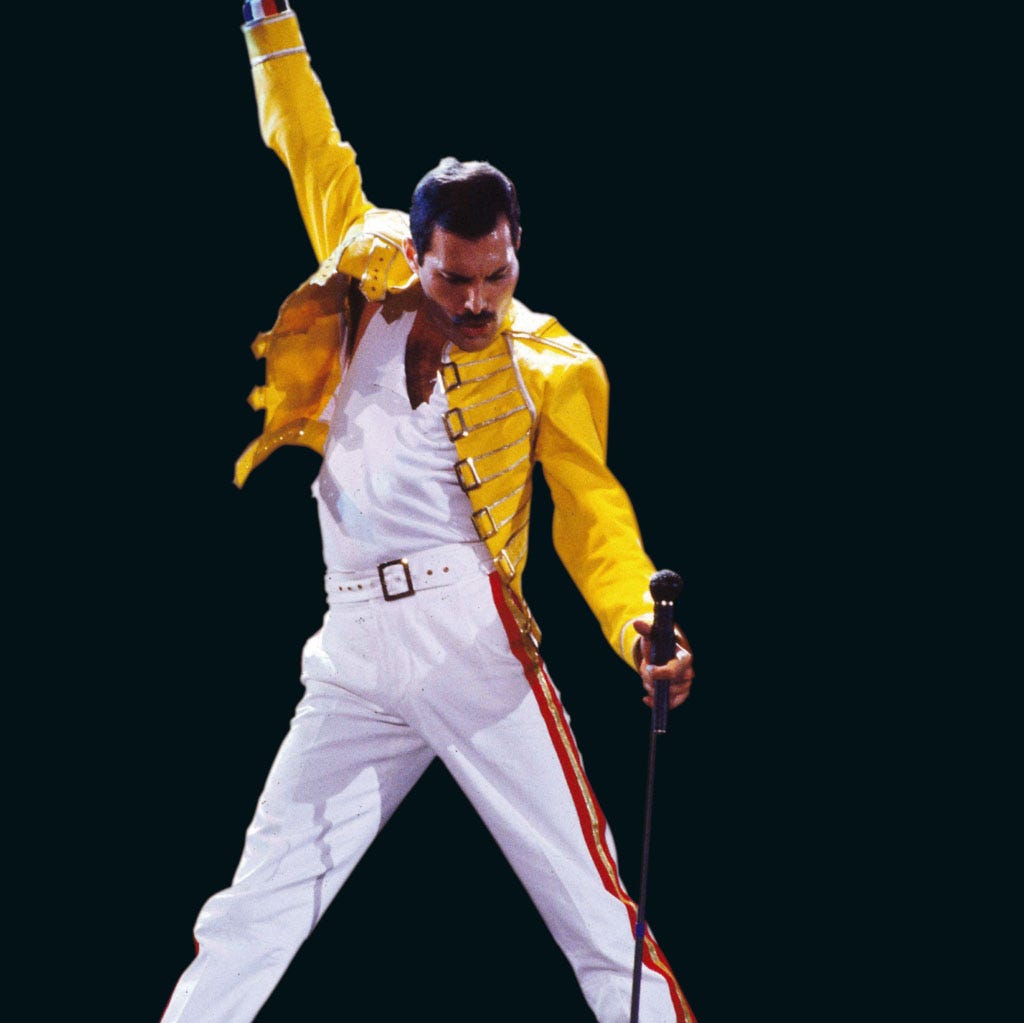

To quote (Zoroastrian) Freddie Mercury, “This could be heaven for everyone, this world could be free, this world could be one” – never stop dreaming, because nature is abundant and infinite and so are you.